In today’s digital age there are many playback methods available to listen to all your favorite music, and we’ve seen a lot throughout the years — records, cassettes, CDs, MP3s, and now streaming. While many of these listening formats have come and gone, there’s just something about vinyl records that can’t be duplicated. Vinyl records were first introduced in 1948 and are still a popular playback method until this day. From their beautifully designed album covers, to the crisp sound when the needle touches the record, and the nostalgic experience they often give, many argue there’s nothing like the experience of classic vinyl records.

If you’re familiar with vinyl records, you may be curious as to how a vinyl disk can produce sound. Well, we’ve taken the guesswork out of it for you. Here we’ll go over the ins and outs of vinyl so the next time you put on a record, you may even appreciate it a little bit more.

Sound Waves

To fully understand how a vinyl record actually works, you need to first understand how a sound wave works. Sounds are created by waves of vibrations that move through the air as vibrating particles. These vibrating waves carry energy from the source of the sound, outward in every direction and finally to our ears. Our ears detect these sound waves because these vibrating particles also vibrate our eardrums. The grooves on a vinyl record are essentially a fingerprint of a sound wave that produces sound when played.

Spiral Grooves

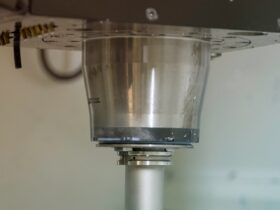

When a final music playlist is created, it is played back in a studio while its signal is dispelled into a disc cutting lathe. This device transfers the audio signal into a continuous spiral groove of a coated master disc with a diamond needle, representing an analog version of a sound wave. The continuous spiral groove is etched into the master disc starting from the outside until it reaches the inside. The width and depth of the spiral groove is an impression of both the frequencies and amplitude of the particular sound wave, while the left and right side of the groove depicts unique stereo sound information. A lot of audio information is critically compacted into each groove. If you were to unravel this spiral groove into a straight line, it would be roughly 500 meters long! Once this final master disc is created with the disc cutting lathe, it is used to create a metal stamper, which has ridges instead of grooves and is essentially a “negative” or inverted copy of the master disc. From this metal stamper, a hydraulic press is used to imprint the grooves into vinyl discs which are finally cooled with water, creating the final product — a vinyl record.

Playback With A Record Player

While the continuous spiral groove of the vinyl record creates this sound wave, it can’t play on its own. The grooves need to be transformed back into sound waves for our ears to detect music with a record player, commonly known as a turntable. A record player is an electromagnetic device that converts sound vibrations into electrical signals. There are many important parts to a record player and when put together, they have the ability to playback music and produce sound.

When a vinyl record is placed on a record player, a stylus, or diamond needle, which is the smallest, yet arguably the most important part of a record player, moves through the etched grooves of the vinyl record. While the record spins, the stylus reads the unique sound waves and audio information created by the grooves vibrations. These vibrations picked up by the stylus needle transfer to the cartridge which converts the energy into an electrical signal that is carried through an amplifier, ultimately producing the music that we hear.

The sound quality of a vinyl record can vary based on the record player you use for playback. According to the turntable experts at Selby in AU, “To fully appreciate a vinyl record and preserve it’s audio quality, it’s key to use a high-quality record player. With the surge in interest in vinyl, we’ve seen quite an increase in demand for higher-end equipment. It truly does make a difference in the listening experience.”

Leave a Reply